The stoat Mustela erminea L. as a historic predator in Worcestershire

P.F. Whitehead

Pictures ©Paul Whitehead.

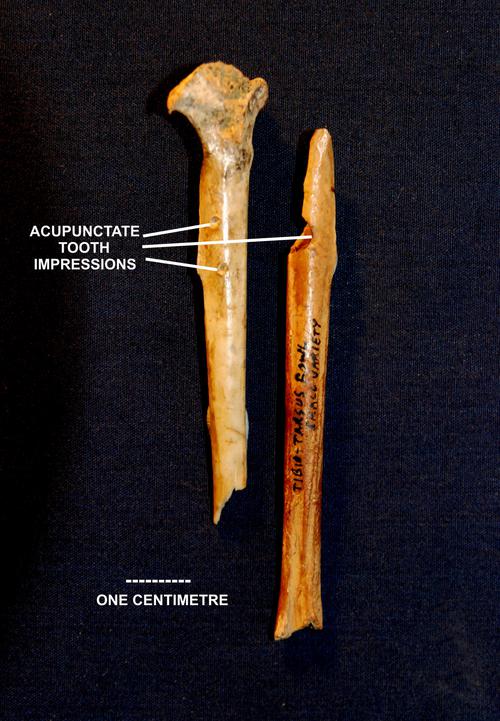

Two bird bones from Romano-celtic Kemerton (found on 11 December 1971) and medieval Pershore (Whitehead & Vince, 1979) show evidence of predation. The bones are both tibiotarsi of domestic fowl (Gallus gallus ssp. domesticus L., Fig. 1.). The tibiotarsus is the principal leg bone which equates anatomically with the mammalian tibia. Fig. 1. shows the two bones in their life positions, the distal articulation of the medieval bone (on the left) and both articulations of the Romano-celtic bone, dating to circa AD250, having been anciently sheared off. The medieval specimen, dating to the period AD1200-AD1300, shows a pair of well-marked tooth impressions as well as various superficial surface markings whilst the earlier specimen shows surface punctures effected with such strength that the bone fragmented.

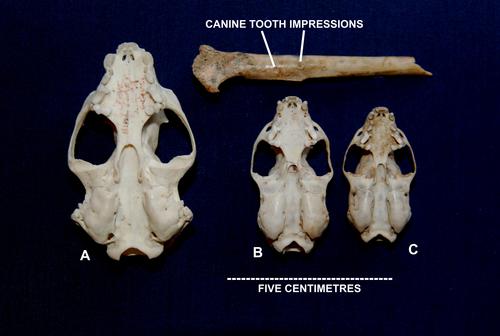

Given the reasonable assumption that these paired impressions are those of a carnivorous mammal I applied the canine dentition of a range of carnivore skulls to them of which mustelids proved a convincing match. The upper canines of a large male Weasel (or Least Weasel Mustela nivalis L., Fig. 2.) did not match perfectly but those a Stoat (M. erminea L., Fig. 3.) did and this is taken to be the predator in both cases. The larger Stoat has the ability to exert substantial and continuing pressure on the bones of its prey whilst the Weasel, in examples seen, leaves something of more 'sewing machine'-like bite traces, and is generally limited to smaller prey with less robust skeletons. Fig. 4 confirms the relative sizes of the skulls and dentition of three mustelids, the Ferret Mustela putorius ssp. furo L., Stoat and Weasel in relation to the medieval bone.

These records of Stoat kills extending back in time to the early Historic Period provide the earliest primary evidence of the occurrence of Stoat in Worcestershire. The relationship between wild animals and society in Romanised and medieval Worcestershire will have been somewhat different to now. In relative terms, the value of a domestic fowl would have been infinitely greater. It is impossible to say whether the medieval birds were managed resources of Pershore Abbey, although given the situation within the curtilage of the Abbey estate (Whitehead & Vince, 1979) this seems probable. It is at least uncertain that commoners had the time and resources to manage fowls within a system of land use very different to the modern one. At Kemerton, fowl bones were thrown into rubbish pits and the birds apparently wandered amongst a nucleated settlement sited on land above the Carrant Brook. In both cases the fowls were of small type (those from Kemerton being slightly the smaller), not unlike those kept recently in some remote parts of southern Europe, the eating of which is quite different and distinctly superior to that of most modern breeds.

A single Buzzard Buteo buteo L. bone was also found in the medieval sediments at Pershore; this is an opportunistic species which may well have been attracted by the presence of managed fowls.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the late Don Bramwell for his assistance in identifying bird bones.

Reference

Whitehead, P. F. & Vince, A.G., 1979. An abandoned Flandrian river channel at Pershore, stratigraphy pottery and biota. Vale of Evesham Historical Society Research Papers 7:9-24

Images

Fig. 1. Tibiotarsi of medieval (on left) and Romano-celtic domestic fowl from Worcestershire showing tooth impressions of a Stoat.

Fig. 2. Canine teeth of a large male Weasel skull in relation to canine tooth impressions on a tibiotarsus of a domestic fowl from medieval Pershore.

Fig. 3. Canine teeth of a Stoat skull in relation to canine tooth impressions on a tibiotarsus of a domestic fowl from medieval Pershore.

Fig. 4. Skulls in palatal view of Ferret (A), Stoat (B) and Weasel (C) in relation to canine tooth impressions on a tibiotarsus of a domestic fowl from medieval Pershore.