Disentangling derivation: Palaeolithic artefacts and biota from Avon No. 4 terrace at Twyning, Gloucestershire

Paul F. Whitehead

Moor Leys, Little Comberton, Pershore, Worcestershire WR10 3EH email: paul@thewhiteheads.eu

Introduction

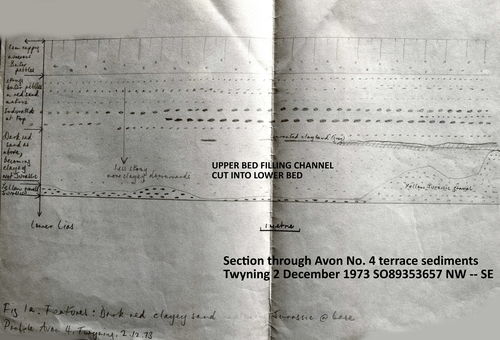

The River Avon terraces at Twyning, Gloucestershire (Dreghorn, 1967; Whitehead, 1988; 1992; Russell & Daffern, 2014) are critically important in sequencing Pleistocene stratigraphy and biotic turnover in the catchment. The sediments under Avon No. 4 and Avon No. 2 terrace surface at Twyning are separated by a river-cut anciently-weathered bedrock bluff (Whitehead, 1992). Each has a full glacial biota at its base, the older terrace sediments having been soliflucted over the surface of the younger one. This contribution attempts to use biotic and artifactual evidence to throw light on processes and time-scales; it is a discussion document and is not conclusive in all respects. The sections in Avon No. 4 terrace at Twyning were centred on SO895365 where the terrace flanked a low hill to the north of Church End Farm. Two contrasting distinct lithofacies (Whitehead, 1992) were subsequently termed an Upper Bed and a Lower Bed within the Twyning Member of the Avon Valley Formation (Whitehead, 2014). In 1973 I did not possess even a single lens reflex camera so those images used here are no more than indicative of what was observed more than 40 years ago. I first visited Twyning Gravel Pit on 5th December 1972 and made 74 visits to the site up to 7th June 1975 with only very occasional visits after that.

Avon No.4 terrace at Twyning

The Lower Bed of fluvial origin was composed of Jurassic-rich well-rounded well-sorted current-bedded Oolitic Limestone gravel. Its surface was variably eroded, in places almost to the base (02), and unconformably overlain by the Upper Bed (01, 02, 03) composed of ferruginous locally cohesive quartz sand, silty and clayey sand and sandy gravel all fining upwards with many large clasts distributed haphazardly at its base. Some of the pebbles had their long axes disposed vertically in a finer matrix. The largest boulder of Uriconian nodular rhyolite (14b) was calculated to weigh ca 356 kgs by Professor F. W. Shotton F.R.S. The Lower Bed contained at its base evidence of a ‘full-glacial’ mammal fauna (Whitehead, 1992) (12) and a significant Mousterian or Middle Palaeolithic flint artefact (vide infra). Otherwise this discussion centres on the Upper Bed only.

Broadly contemporary fossils from the Upper Bed

The only broadly contemporary biotic evidence from the Upper Bed is provided by a single valve of the freshwater bivalve mollusc Corbicula fluminalis (O. F. Müller, 1774) (Veneroida, Corbiculidae) (04a, 04b) here illustrated for the first time. On the basis of its condition Whitehead (1992) failed to see how it could be far-derived and was confronted with the problem of how to explain significantly conflicting biotic evidence from beneath one terrace surface. He could have looked for a mechanism which might have explained that but the compounded knowledge base of British Quaternary science then was far from what it is now.

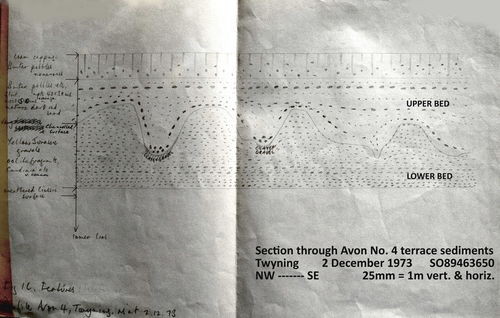

Otherwise the fossils are limited to Palaeolithic artefacts which number 25 (Whitehead, 1988) almost all of which can be ascribed to the Lower Palaeolithic (Whitehead, 1988). Mostly they are weathered, rolled, abraded or broken. Twenty of these, now in the collections of the British Museum, London, were recently reviewed by Russell & Daffern (2014). The artefacts include an impressive Acheulian handaxe fashioned in Upper Greensand Chert depicted here for the first time (05, 06). The singular importance of this artefact is that its appearance at Twyning is accredited at least partially to human rather than natural processes (Whitehead, 1988). The petrology was determined from thin section cut by Professor F. W. Shotton F.R.S. and the immaculately restored section is indicated on 05, 06. It will be observed that this handaxe is in fresh unweathered condition and somewhat lustrous.

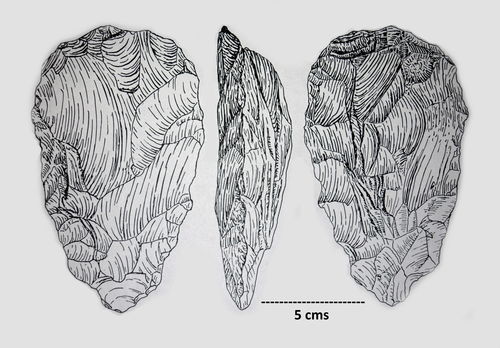

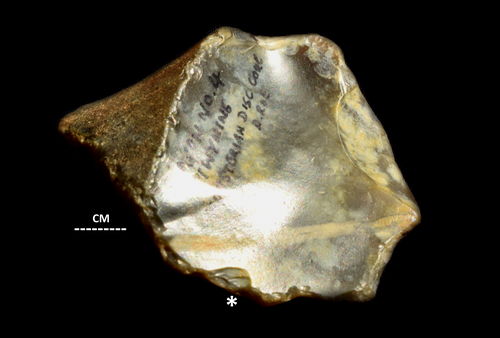

A second key palaeolith from the Upper Bed at Twyning (07, 08, 09) is up to now unpublished for good reason. The piece is a large single convex side scraper with scalar or Quina retouch (following Debénath & Dibble, 1994) found on 2 December 1973 and superbly executed. It is also extraordinarily well preserved although one corner was removed mechanically in the gravel pit. Like the valve of Corbicula fluminalis it raises numerous questions; its distinctive typology and technology render it unlike all other English midland palaeoliths seen by me with the somewhat tenuous exception of some Late Middle Palaeolithic pieces from the Carrant valley with which it can bear no time relationship. When Whitehead (1988) described the Twyning Lower Palaeolithic assemblage this artefact was set aside on grounds of anachronism. It created a great deal of head-scratching and was not then considered to be Lower Palaeolithic, especially since a Middle Palaeolithic artefact (vide infra) was known to exist at the base of the Lower Bed at Twyning. Forty two years ago it was supposed that this scraper was also Middle Palaeolithic (Bordes, 1968; Roe, 1981); discussion with Professor Derek Roe during 1982 when mention of the High Lodge flake industry, ‘Quina-retouch’ and ‘Charentian’ was also made, did not change that.

Patination of flint artefacts across the time span of the Avon Valley Formation conveys useful comparative information about their ages and history in a generalised sense. In that and other ways, this scraper presents many challenges. Blunting of the functional edge (09) is scarcely evident and there are no post-manufacturing or post-depositional modifications to it other than the recent mechanical damage (07). Possibly it was sealed in alluvial or lacustrine sediments, which provide notable preservative properties, for an extended period.

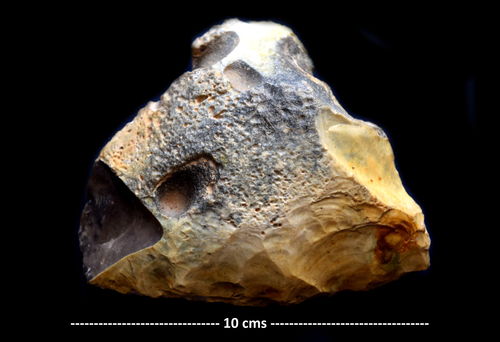

Middle Palaeolithic artefact from the Lower Bed

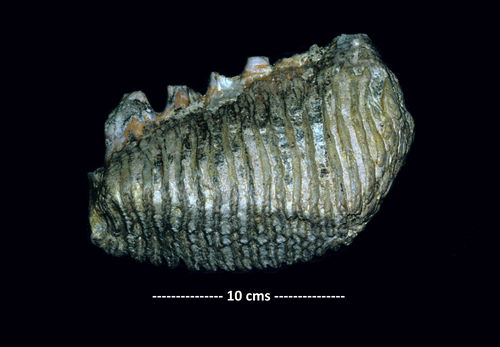

A further hitherto unpublished key artefact from Twyning (10, 11) was found in situ at the base of the fluvial Lower Bed sediments on 11 March 1973. This bed contained the full-glacial biota ascribed by Whitehead (1992, 2014) to Marine Isotope Stage 6 (MIS 6). The artefact is a Middle Palaeolithic or Mousterian disc core in good quality black flint showing minor traces of retouch and utilisation along one straightened edge. The remaining nodular surface shows no evidence of cold climate weathering and the artefact is in fresh condition. The identity was confirmed by Professor Derek Roe during 1987. This artefact therefore fills a gap in the Avon valley hominin record by confirming a regional presence approaching the climatic nadir of MIS 6 in spatial association with the entrained ‘mammoth-steppe’ megafauna (12, 13). It is especially important for its ability to discriminate between hominin temporal affinities within the sediments of Avon No. 4 terrace and their contemporaneous biota and between the same affinities demonstrated by the many older palaeoliths found derived elsewhere in Avon No. 4 terrace but more usually on its surface (Shotton, 1983).

Derived knowledge from derived fossils

This discussion is limited to three specific fossils from the Upper Bed, namely the bivalve mollusc, chert handaxe and flint scraper already cited. An attempt is made to provide a working hypothesis for the mechanics of deposition using combined evidence threads.

Corbicula fluminalis (O. F. Müller) (Veneroida, Corbiculidae)

According to Penkman et al. (2013) the Upper Bed valve of Corbicula fluminalis (O. F. Müller), a warm-temperate bivalve mollusc, can be no younger than MIS 7 but the Lower Bed at Twyning is held to mark MIS 6 time. Given that the Upper and Lower Bed underlie a single terrace feature the C. fluminalis must therefore be derived. It is very difficult to conceive that this shell could have passed through multiple cycles of derivation. According to Penkman et al. (2013): “The pattern of occurrence of Corbicula in various terrace sequences indicates that it was present [in Britain] during the latter part of MIS 11, in MIS 9 and MIS 7 but not in MIS 5e” thus agreeing with Meijer & Preece (1995).

Palaeolithic artefacts

The same comment regarding derivation must apply to all the Palaeolithic artefacts (Whitehead, 1988) including the Greensand Chert Acheulian handaxe (05, 06) and the convex side-scraper (07, 08, 09). Both are unusual in having acquired a secondary lustre, especially marked in the scraper, but neither are ventefacted. Recent evidence (Bates et al., 2014) has indicated that Acheulian handaxe technology survived in Britain until MIS 8 time which provides a current terminus ante quem for dated British Acheulian sites and evidence that basic lithic technologies overlap significantly in time.

Whitehead (1992) listed the provenance of a range of clasts found mostly near to the base of the Twyning Upper Bed. These formed a significant feature in the field (Fig. 13) and can only have been brought to Twyning by an ice sheet moving around the northern edge of the Malvern Hills from the north-west. They are all unquestionably derived from glacial till. It is therefore to the north-west that we should look for the provenance of the palaeoliths and Corbicula fluminalis valve and not upstream in the River Avon valley as suggested by Russell & Daffern (2014). The ice-sheet that produced this till cannot be regarded as the Devensian one which marked its southern English limit with terminal moraines much further north (Sparks & West, 1968; Rose, 2014). This matter requires discussion.

There is empirical evidence to underpin that the Corbicula fluminalis valve is no younger and almost certainly no older than MIS 7 and that the Acheulian handaxe need not be significantly older than MIS 8 (Bates et al., 2014). The problematical flake scraper (Figs 7, 8, 9) is a very different matter. I understand that it may be unwise to place undue weight on a single lithic artefact but there are evidently close techno-typological affinities between it and elements of the High Lodge flake-tool assemblage from Mildenhall in Suffolk. Were that not to be regarded as unduly fanciful this piece would predate the Anglian glaciation of Britain and could occupy MIS 13 time. As such it would provide the only evidence in the Avon valley, in Worcestershire or in Gloucestershire of any artefact associated with the pre-Anglian Bytham river catchment. It would thus convey the intriguing possibility of upstream penetration of the High Lodge flake-tool industry as far north as the English midlands. Such a hypothesis would place the age of the scraper in broad terms about 530ka. There is no simple way for me to prove this and dismiss the possibility of a true Middle Palaeolithic age; the matter is here merely thrown open with due regard to the regional uniqueness of the piece. My own view is that a pre-Anglian age is the more likely.

The High Lodge flake artefacts from Mildenhall even now remain a challenge to students of palaeolithic archaeology (Pettitt & White, 2012) and have done so for long; the same challenge faced Professor Roe and myself 33 years ago with regard to this flake-scraper. Breuil (1932) ascribed High Lodge artefacts to the Clactonian and figured them in some detail; his Figure 15 serves to illustrate the similarities mentioned. Breuil (1949) believed that the artefacts occupied Hoxnian time. Stringer (2006) emphasised the continuing typological difficulties surrounding the High Lodge flake tools and noted acceptance of the fact that their relationship lies with the Bytham river and with MIS 13 time.

How can it be that three derived fossils, between them perhaps spanning >300ka of time, can all be preserved so remarkably in one aggradation held to have been deposited in MIS 6 time at Twyning in Gloucestershire? I believe that the sediments containing them provide the clue noting (01, 13) that they include sand with an abundance of finer particles rendering them cohesive; it may come as a surprise to consider that glacigenic processes may in special circumstances actually conserve material evidence of a fragile nature. Slow dispersal during ice sheet ablation processes, including mass movement of frozen or semi-frozen sediment on a landscape scale, could have created the lustre observed on both the handaxe and the scraper (09).

Stringer (2006), in describing the situation at High Lodge, is precisely relevant viz.: “ ……….the deposits that contained these artefacts were probably from an interglacial lake or river that was frozen solid in the subsequent Anglian ice-age and was bulldozed miles across Norfolk enclosed within glacial debris as a gigantic glacial erratic.” This is analogous to the situation at Twyning with the ablating front of a MIS 6 ice sheet lying not far north of the site assembling a range of earlier glacigenic deposits somewhat above the valley of the modern river at that point. Wills (1951) constructed a penultimate glacial ice sheet map of the British Isles which by his own admission was not certainly definitive. According to Wills (1951): “The main drainage from the ice in S. England was carried by the Avon-Lower Severn……………….” His map shows an invagination in the ice sheet following the axis of that drainage which lends further credence to the ‘bulldozing’ concept and places the edge of the ice sheet close to Twyning. Subsequent research synthesised by Jones & Keen (1995) broadly confirmed the position of the ice sheet front. More recently Rose (2014) has stated that tills derived from MIS 6 ice sheets have yet to be recognised in Britain; that being so Twyning would seem to hold a key position in British Quaternary studies.

Shotton (1988) provides a rationale for how palaeoliths might be assembled and sorted by the episodic retreat and readvance of Middle Pleistocene ice sheets further north in the English Midlands. Those palaeoliths are now known to be older in real terms than he may have anticipated, perhaps significantly older than the Anglian glaciation, and it is noted that he makes no reference to any derived palaeoliths showing affinity with High Lodge flake tools. If it was quartzite pebble tools of this age which were subsequently recycled into the Avon valley, observing the Bramcote Hill concentration (Shotton, 1988), then the hominin presence in central England prior to the Anglian glaciation must have been substantial.

The periglacial ‘bulldozing’ effect at Twyning was powerful enough to move glacial erratic rocks weighing as much as ca 356 kilograms (14a, 14b) perhaps invoking the mechanism of ice-rafting. Quoting the general observation of Imbrie and Imbrie (1979): “The blanket of sediment that the glacier left behind when it finally retreated was a chaotic jumble of unstratified and stratified deposits” and it is this that finally became the Upper Bed at Twyning. Ice-sheet ablation could be employed to explain the palaeochannels cut into the Lower Bed. Some of the channels sketched in the field were relatively steep-sided (03) and could be explained by variation in permafrost state over time and the refreezing of water contained within them; that would explain the downturned gravel strings (03) observing that intraformational ice wedge casts were also observed at that level (Whitehead, 1992).

Summary

At Twyning

1. The Lower Bed beneath Avon No. 4 terrace surface aggraded by fluvial processes in MIS 6 time and contains a cold climate biota and a fresh unworn Middle Palaeolithic disc core (Whitehead, 1992 and this paper).

2. A MIS 6 ice sheet with its southern limit lying close to Twyning ablated episodically during late MIS 6 time and in so doing removed an unknown thickness from the Lower Bed and cut channels into it. The same process deposited an Upper Bed, subject to intraformational ice wedge pseudomorphs, containing fossils, including palaeoliths, from of a variety of pre-MIS 6 age Quaternary superficial deposits within range of the ice sheet. Analogues might include the Woolridge Gravels (Hey, 1963) which evidently now only occur to the south of Twyning. The scale and extent of cycles of derivation is confirmed by the battered state of many of the derived Lower Palaeolithic artefacts at Twyning.

3. The emplacement of the Upper Bed appears not to have been uniform either in space or time. There is evidence from sections of a hiatus between the development of the erosion surface of the Lower Bed and the aggradation of the Upper Bed in places.

4. A valve of Corbicula fluminalis in the Upper Bed is probably of MIS 7 age and is unlikely to be far-travelled and may have been protected by movement in frozen or semi-solid fine-grained or highly-structured sediments.

5. A flake-scraper from the Upper Bed is provisionally held to be pre-Anglian possibly of MIS 13 age. The high overall lustre of this scraper could be explained by slow transportation over a range of gradients in a cohesive matrix of semi-frozen or frozen fine-grained or highly-structured sediment.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge Professor Derek Roe [d1] for his constructive input and in particular Professor F.W. Shotton F.R.S. [d2] both for underpinning some aspects of this study and for providing an unending source of informed discussion in the field. The practical support of Mr T. E. Spry [d3] and the staff of Western Aggregates Ltd is remembered with gratitude [d1 = deceased 24.9.2014; d2 = deceased 21.7.1990; d3 = deceased 9.4.2012].

References

Bates, M.R., Wenban-Smith, F.F., Bello, S.M., Bridgland, D.R., Buck, L.T., Collins, M.J., Keen, D.H., Leary, J., Parfitt, S.A., Penkman, K., Rhodes, E., Ryssaert, C. & Whittaker, J.E., 2014. Late persistence of the Acheulian in southern Britain in an MIS 8 interstadial: evidence from Harnham, Wiltshire. Quaternary Science Reviews 101:159-176.

Bordes, F., 1968. The Old Stone Age, pp. 1-255.

Weidenfield & Nicholson, London.

Breuil, H., 1932. Les industries a éclats du Paléolithique Ancien 1. Le Clactonien. Préhistoire 1(2):125-190.

Breuil, H., 1949. Beyond the bounds of history, pp.1-100.

P.R. Gawthorn Ltd, London.

Debénath, A. & Dibble, H.L., 1994. Handbook of Palaeolithic Typology 1. Lower and Middle Palaeolithic of Europe, pp. i-ix, 1-202. University of Pennsylvania.

Dreghorn, W., 1967. Geology explained in the Severn Vale and Cotswolds, pp. 1-191. David & Charles, Newton Abbott.

Hey, R.W., 1963. The Pleistocene history of the Malvern Hills and adjacent areas. Proceedings of the Cotteswold Naturalist’s Field Club 33:185-191.

Imbrie, J. & Imbrie, K.P., 1979. Ice ages: solving the mystery, pp. 1-224. The Macmillan Press Ltd, London.

Jones, R.L. & Keen, D.H., 1993. Pleistocene environments in the British Isles, pp. i-xvi, 1-346. Chapman & Hall, London.

Meijer, T. & Preece, R.C., 1995. Malacological evidence relating to the insularity of the British Isles during the Quaternary, pp. 89-110 in: Preece, R.C. (ed.), Island Britain: a Quaternary perspective. Geological Society Special Publication 96.

Penkman, K.E.H., Preece, R.C., Bridgland, D.R., Keen, D.H., Meijer, T., Parfitt, S.A., White, T.S. & Collins, M.J. 2013. An aminostratigraphy for the British Quaternary based on Bithynia opercula. Quaternary Science Reviews 61:111-134.

Pettitt, P. & White, M., 2012. The British Palaeolithic: human societies at the edge of the Pleistocene world, pp. i-xx, 1-592. Routledge, Abingdon.

Roe, D.A., 1981. The Lower and Middle Palaeolithic Periods in Britain, pp. i-xvi, 1-324. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Rose, J., 2014. Middle Pleistocene glaciations in Britain and northwestern Europe. pp. 197-224 in: Catt, J.A. & Candy, I. (eds), The history of the Quaternary Research Association, London.

Russell, O. & Daffern, N., 2014. Putting the Palaeolithic into Worcestershire’s HER: creating an evidence base and toolkit. Archive and Archaeology Service Worcestershire County Council.

Shotton, F.W., 1983. United Kingdom contribution to the International Geological Correlation Programme: Project 24 Quaternary glaciations of the northern hemisphere. Quaternary Newsletter 39:19-25.

Shotton, F.W., 1988. The Wolstonian geology of Warwickshire in relation to Lower Palaeolithic surface finds in north Warwickshire in: MacRae, R.J. & Moloney, N., Non-flint stone tools and the Palaeolithic occupation of Britain. Bulletin of Archaeological Research. British Series 189:103-122.

Sparks, B.W. & West, R.G., 1968. The ice age in Britain, pp. i-xvii, 1-302. Methuen & Co. Ltd.

Stringer, C., 2006. Homo britannicus the incredible story of human life in Britain, pp. 1-319. Allen Lane, London.

Whitehead, P.F., 1988. Lower Palaeolithic artefacts from the Lower valley of the Warwickshire Avon in: MacRae, R.J. & Moloney, N., Non-flint stone tools and the Palaeolithic occupation of Britain. Bulletin of Archaeological Research. British Series 189:103-122.

Whitehead, P.F., 1992. Terraces of the River Avon at Twyning, Gloucestershire; their stratigraphy climate and biota (with Appendices 1 & 2). Quaternary Newsletter 67:3-29.

Whitehead, P. F., 2014. An exposure in the Pershore Member of the Avon Valley Formation at February Piece, Allesborough Hill, Pershore, Worcestershire. Worcestershire Record 37:36-45.

Wills, L. J., 1951. A palaeogeographical atlas of the British Isles and adjacent parts of Europe, pp. 1-64. Blackie & Son Ltd, London & Glasgow.

Images

01. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Upper and Lower beds SO895366, 18 May 1974.

02. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire. Field sketch 2 December 1973 showing the Lower Bed almost removed by ice sheet meltwater channelling then infilled with Upper Bed sediments.

03. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire. Field sketch 2 December 1973 showing palaeochannels on the surface of the Lower Bed. The implication is that the channels were ice-filled before the Upper Bed sediments were laid down and subsequently let down into them.

04a. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Upper Bed 3 May 1973. Right valve of Corbicula fluminalis (O. F. Müller) upper surface.

04b. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Upper Bed 3 May 1973. Right valve of Corbicula fluminalis (O. F. Müller) inner surface.

05a. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Upper Bed SO89453650, 17 December 1972. Acheulian Handaxe of Upper Greensand Chert as in 06.

05b. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Upper Bed SO89453650, 17 December 1972. Acheulian Handaxe of Upper Greensand Chert as in 06. The dashed line marks the position of the infilled section cut and restored by Professor F.W. Shotton F.R.S.

06. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Upper Bed SO89453650, 17 December 1972. Acheulian Handaxe of Upper Greensand Chert especially delineated by Professor F. W. Shotton F.R.S.

07. Avon No 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Upper Bed SO894366, 2 December 1973. Lower Palaeolithic single convex side scraper with scalar or Quina retouch. Cortical surface of flake from one of the most provocative palaeoliths yet to be found in the English midlands.

08. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Upper Bed SO894366, 2 December 1973. Lower Palaeolithic single convex side scraper with scalar or Quina retouch. Flake surface with distal end struck off to create an index finger rest.

09. Avon No 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Upper Bed SO894366, 2 December 1973. Lower Palaeolithic single convex side scraper with close up of scalar or Quina retouch (grey colour in the flake scar steps result from casting by Professor F.W. Shotton F.R.S.).

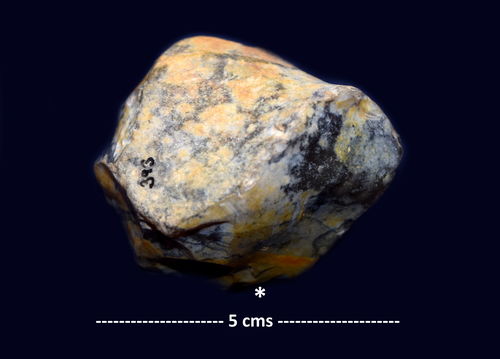

10. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Lower Bed SO895365, 11 March 1973. Middle Palaeolithic Mousterian disc-core with one edge (marked *) retouched, straightened and utilised.

11. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, Lower Bed SO895365, 11 March 1973. Middle Palaeolithic Mousterian disc-core with one edge (marked *) retouched, straightened and utilised. Reverse of 10.

12. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, base of Lower Bed, Woolly Mammoth Mammuthus primigenius Blumenbach. Intensely comminuted distal portion of tusk in situ SO89423655 2 February 1974.

13. Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, base of Lower Bed, Woolly Mammoth Mammuthus primigenius Blumenbach.: Upper M3 of mature remarkably small animal, SO894365, 19 April 1973.

14a Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, SO89503660 18 May 1974. Glacial erratic boulders in situ base of Upper Bed.

14b Avon No. 4 terrace, Twyning, Gloucestershire, SO89503660 18 May 1974. Glacially transported boulder of Uriconian Nodular Rhyolite weighing ca 356 kilograms 26 July 1973 from this provenance (14a), the base of Upper Bed.