The spread of Northern Ravens Corvus corax in Worcestershire

Mike Metcalf. mikebirder@hotmail.com

Ravens have been seen with increasing frequency right across Worcestershire in recent years. Brett Westwood wrote about this as an exciting new phenomenon in 1996, and the British Trust for Ornithology’s (BTO) latest Bird Atlas (2007-11) confirms a national range expansion to the east, matching that of the Common Buzzard Buteo buteo. Only eastern Britain from Inverness to Essex has yet to be populated by this most adaptable of species as it exploits “pastoral or mixed lowland farmland and forestry” (Balmer et al 2013). It is therefore small surprise that Worcestershire has been part of this range expansion.

The upland sheepwalks in north and central Wales have recorded the highest density of Ravens in Europe (Dare 1986) and the BTO’s Breeding Bird Survey data indicate that these areas were a source for the expanding populations along western English counties until 2005. The density of Ravens in the source areas outstripped the availability of food and nest sites, forcing juveniles and less dominant adults to seek those resources away from the more dominant territorial pairs. After 2005 abundances in these Welsh areas began to fall while western English abundances correspondingly increased, and it is possible that there was then an easterly movement of some of those established breeding pairs (Metcalf 2013.

In mediaeval times, Ravens were frequently associated with English cities (Ratcliffe 1997) and one interesting aspect of the recent trends is the resumption of nesting in urban environments. Since 1996 there are records of nests in Chester, Wigan, Liverpool, Cardiff, Gloucester, Bristol and Plymouth, involving cathedrals, city halls, other large buildings and a tree in a city centre park in Worcester where Ravens are thought to have bred in the Battenhall area in 2012 raising four young. Two observers in that district recorded sightings of between one to five Ravens on 185 days in a 12 month period to June 2013, including frequent examples of multiple observations in one day (Metcalf 2013). Breeding in the city has also been reported in Astwood Cemetery as well as Bevere on the city borders.

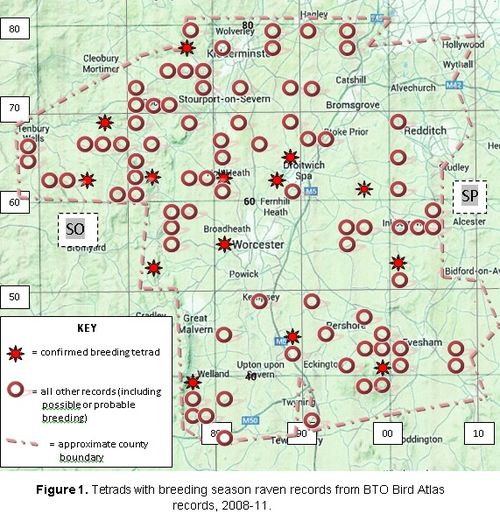

The national trends generated questions for Worcestershire about the numbers and locations of breeding and wintering birds and I investigated these with the BTO Bird Atlas data-set for Hereford and Worcester. Between the winter of 2007/08 and the summer of 2011 nearly all the tetrads (2 × 2km squares) within Worcestershire were surveyed at least once by volunteer bird recorders, providing a four-year long snapshot of breeding and wintering occurrences. I have transposed the results onto maps of the county (01).

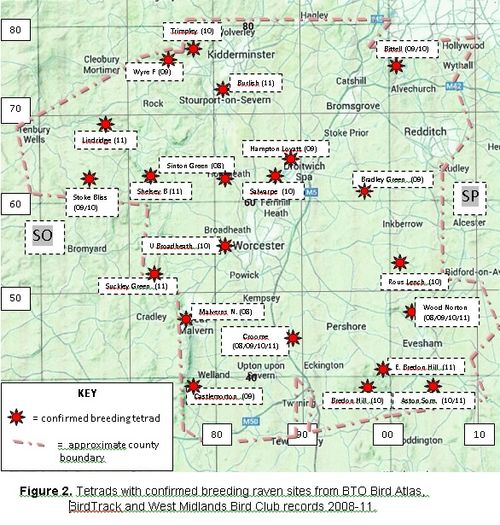

95 (c. 22%) Worcestershire tetrads were occupied of which 14 contained confirmed breeding sites. There is a slight bias to the north and west of the county in these records but this could result from variations in “observer effort” in different areas for the Atlas exercise. During the same period, there were a small number of additional confirmed breeding records from BirdTrack and the West Midlands Bird Club in the east and south of the county. These were added to produce a more complete picture of the confirmed breeding sites (02).

This increases the breeding sites to 21. I t is not possible to accurately establish the number of breeding sites in each year as it is highly unlikely that all tetrads were surveyed in each year. However, the numbers for 2009, 2010 and 2011 were eight, ten and eight respectively, and these totals can be regarded as the minimum number of breeding pairs in the county during those years. This compares with Brett Westwood’s estimate of four breeding pairs in the county in 1996.

The West Midlands Bird Club Annual Report in 1998 reported 57 Worcestershire localities from which Ravens were reported throughout the year and noted that most were west of the Severn, illustrating the easterly extension of the range in the subsequent decade.

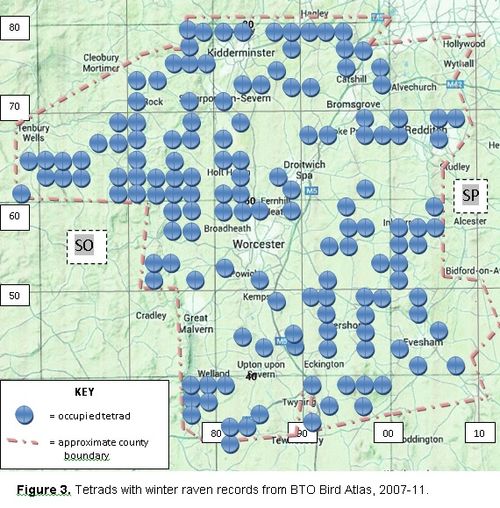

In winter, Ravens are more widely distributed across the county (03). The Atlas data record 146 occupied tetrads (34%), representing a 54% increase over the breeding season distributions.

The highest counts were in the tetrad containing the Throckmorton landfill site north east of Pershore with 24 in November 2010 and 35 in February 2011. Ravens have been observed exploiting landfill food waste for many years (Ratcliffe 1997) and counts of 31 and 48 were recorded for the Birds of Gloucestershire (Kirk & Phillips 2013) adjacent to the two major sites in that county. Over the past two decades, however, vigorous environmental policies have resulted in a steady reduction in all biodegradable municipal wastes going to landfill (Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 2009) and this bounty for Ravens (and gull species) is set to diminish further as progress towards national targets continues.

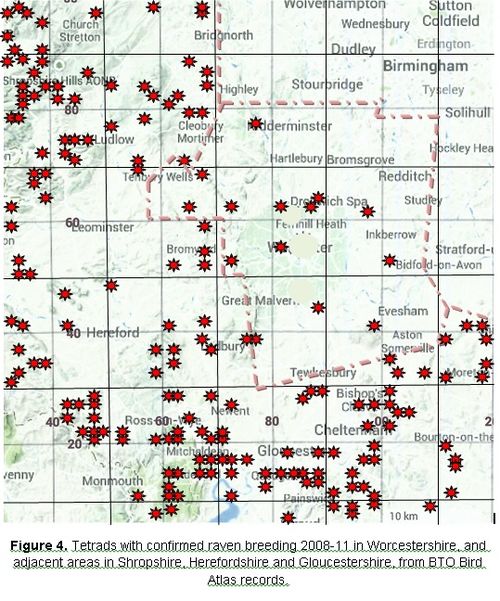

The Welsh hills hosted the populations that generated the original range expansion into western England at least until 2005, but what specifically drove the increases in Worcestershire? Data for the distribution and abundance of Ravens in neighbouring counties might throw some light on this, and map 04 shows confirmed breeding sites in adjacent parts of Shropshire, Herefordshire and Gloucestershire, alongside those in Worcestershire (04).

Once again this map shows a four-year snapshot rather than an annual one, but there are clusters associated with areas of higher ground in the Shropshire hills, the Forest of Dean, the Wye Valley and the Cotswolds. Breeding densities are clearly higher than in Worcestershire, raising the possibility that the neighbouring populations have acted as a source for our own county.

Summary

This gives a “position statement” of the extent to which Ravens had established themselves in Worcestershire between the winter of 2007/08 and the summer of 2011. It will be interesting to see how it develops from here, and whether the easterly expansion will continue. What will be the carrying capacity for Ravens in a county such as ours? I hope to find some answers to these questions in future, but in the meantime would welcome any comments and observations from Worcestershire Record readers.

References

Westwood, B. 1996. The Return of the Raven. Wildlife News, Worcestershire Wildlife Trust Newsletter 19th March 1996.

Balmer, D.E., Gillings, S., Caffrey, B.J., Swann, R.I., Downie, I.S. & Fuller, R.J. 2013. Bird Atlas 2007-11: the breeding and wintering birds of Britain and Ireland. BTO Books, Thetford.

Dare, P.J. 1986. Raven Corvus corax populations in two upland regions of north Wales. Bird Study 33, 179-189.

Metcalf, M. 2013. Nevermore? An Investigation into the return of Northern Ravens (Corvus corax) to lowland England. Unpublished dissertation for MSc in Ornithology at Birmingham University.

Ratcliffe, D. 1997. The Raven. T. & A.D. Poyser, London.

West Midland Bird Club. 1998. Annual Report No. 65. West Midland Bird Club.

Kirk, G., & Phillips, J. 2013. The Birds of Gloucestershire. Liverpool University Press, Liverpool.

Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2009. Environmental Permitting: The Landfill Directive for the Environmental Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2007. Updated October 2009, Version 2.0. Published by DEFRA.

Images

01. Tetrads with breeding season records collected for BTO Atlas 2008-2011.

02. Tetrads with confirmed breeding Raven sites from BTO Atlas and other breeding records.

03. Tetrads with winter Raven records from BTO Atlas 2007-2011

04. Confirmed Raven breeding sites in adjacent counties alongside those in Worcestershire. From BTO Atlas data

05. Raven by Ray Bishop