White-Clawed Crayfish Population within the Wyre Forest – 2012 Update

Ann Hill and Graham Hill

Background

A baseline white-clawed crayfish survey of Bell Brook and Forest Lodge Stream, both within the Wyre Forest, was undertaken in 2010. Following the 2010 survey a monitoring programme was set-up to record the white-clawed crayfish in Wyre and in 2011 the first monitoring survey of the two watercourses was undertaken. In addition, surveys were also undertaken of Kingswood Stream and Longdon Stream which were also found to support white-clawed crayfish. During 2012 all four watercourses were surveyed as part of the monitoring programme and this article gives a summary of the survey findings.

The aims of the study are: to build up a record of white-clawed crayfish in watercourses across the Wyre forest; to detect any change in population range, abundance and dynamics; to trigger a response if any changes are undesirable; and to contribute to the knowledge of white-clawed crayfish population within the Wyre Forest, Worcestershire and the UK.

The monitoring targets are: a) Crayfish Population Range: White-clawed crayfish should be present in all four watercourses; and non-native crayfish should be absent from all four watercourses; b) Crayfish Population Abundance: There should be no statistically significant reduction in the number of white-clawed crayfish in the watercourse over three or more years in succession; the relative abundance of white-clawed crayfish in the watercourse should remain relatively constant from year to year; c) Crayfish Population Dynamics: Juvenile crayfish should be present in the watercourse; the proportion of juveniles (<25 mm carapace length) from a healthy population should be about 40%; and male and female white-clawed crayfish should be present in a watercourse.

Method

The 2012 survey replicated (where possible) the same team of surveyors, the same number and location of sample patches (fixed-area sampling) and the same amount of survey effort as surveys undertaken in previous years. The survey work was undertaken by two licensed surveyors and several assistants between 20 August and 18 September 2012 following published guidelines and best practice (Peay 2002).

Site

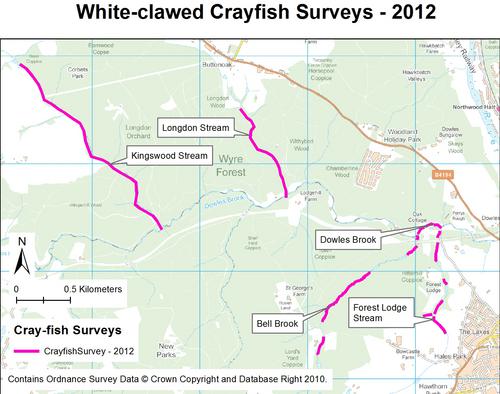

The site and the location of the four watercourses are shown in Fig. 01.

Results

Crayfish Habitat

Bell Brook retained excellent in-stream and bankside habitat. Water clarity was excellent and there was no significant change in water chemistry from the previous year.

Forest Lodge Stream water channel was difficult to access in places due to high water levels caused by heavy rain in the previous 24 hours. Water clarity was excellent and there was no significant change in water chemistry from the previous year.

Kingswood Stream had excellent in-stream and bankside habitat. The in-stream duck pond has been removed. Water clarity was very poor during both the daytime and nocturnal surveys and the habitat had a distinct smell of fertiliser. Water temperature was significantly lower in 2012 compared with measurements taken in 2011. There was no significant change in water pH with the previous year. However, Kingswood Stream had the highest recording of dissolved solids in the water of all four watercourses and levels had increased on 2011 measurements, although not significantly.

Longdon Stream had excellent in-stream and bankside habitat. The water was turbid on both survey visits and water clarity was poor. Longdon Stream had significantly higher water temperature and a significantly lower water pH and concentration of dissolved solids in the water in 2012 compared with measurements taken in 2011. Longdon Stream had the second highest recording of dissolved solids in water of all four watercourses but levels were lower than in 2011.

Crayfish Population Range

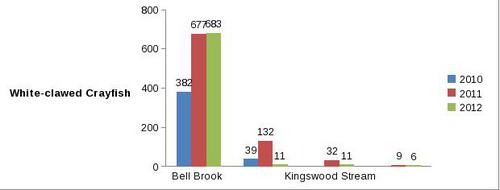

White-clawed crayfish were present in all four watercourses in 2012, Fig. 02. No non-native crayfish were found in any of the watercourses surveyed.

Crayfish Population Abundance

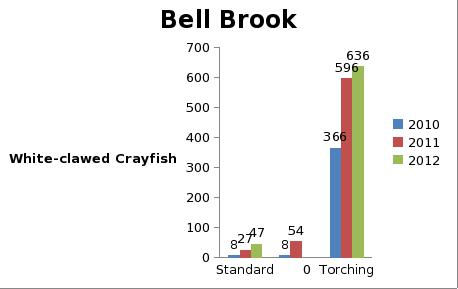

Bell Brook had a statistically significant increase in standard daytime manual observations in 2012 compared with observations in 2010 and 2011 (Kruskal-Wallis test, P-value 0.01), Fig. 03. There was no significant increase in night-time torching observations (Kruskal-Wallis test, total observations P-value 0.125).

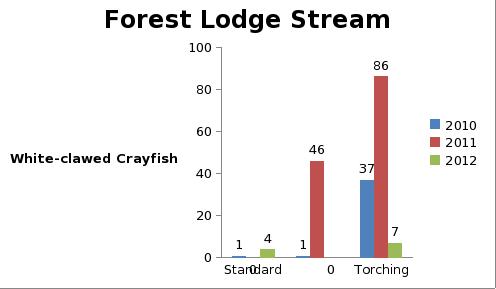

Forest Lodge Stream observations across the three recording years have been very variable because of the influence of flow conditions, Fig. 04. The increase of crayfish observation in 2011 was the result of drought conditions concentrating the white-clawed crayfish into a smaller area and which also provided surveyors with greater access to the stream bed for recording. However, in 2012 the opposite was true and the high water levels limited surveyor access to the stream bed for recording and thereby reduced the survey efficiency. In addition, standard survey effort in 2011 was replaced by a rescue operation. There was a non-significant increase in standard daytime manual observations compared with observations in 2010 and 2011 (Kruskal-Wallis test, P-value 0.737). However, this result has to be tempered by the fact that there no standard survey in 2011.

There was a statistically significant decrease in night-time torching observations in 2012 compared with 2011 observations (Kruskal-Wallis test, P-value 0.042). Nonetheless, when compared with observations from when the monitoring study began, there was a non-significant decrease in night-time torching observations in 2012 compared with observations made in 2010 and 2011 (Kruskal-Wallis test, P-value 0.148).

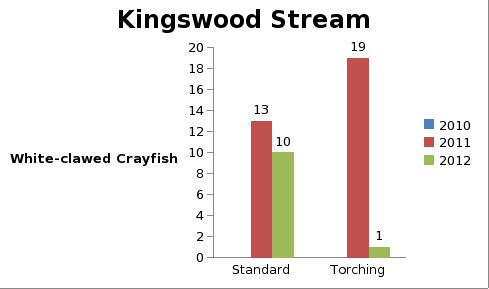

Kingswood Stream had a non-significant decrease in both standard daytime manual observations (Kruskal-Wallis test, P-value 0.494) and in night-time torching observations (Kruskal-Wallis test, P-value 0.246) in 2012 compared with observations made in 2011, Fig. 05.

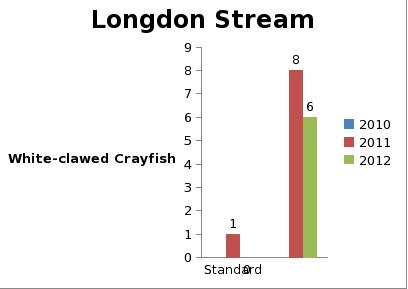

Longdon Stream had a non-significant decrease in night-time torching observations (Kruskal-Wallis test, P-value 0.658), Fig. 06. White-clawed crayfish were undetected using the standard daytime manual observations in 2012 in Longdon Stream.

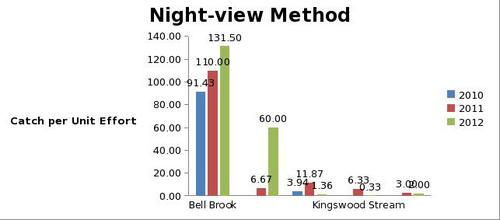

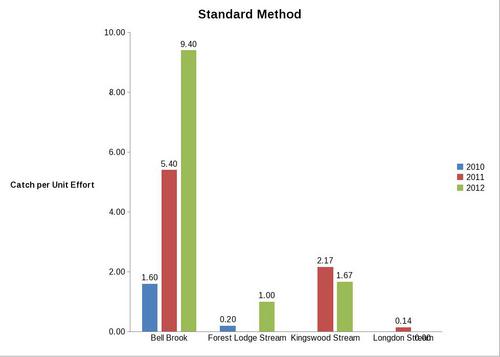

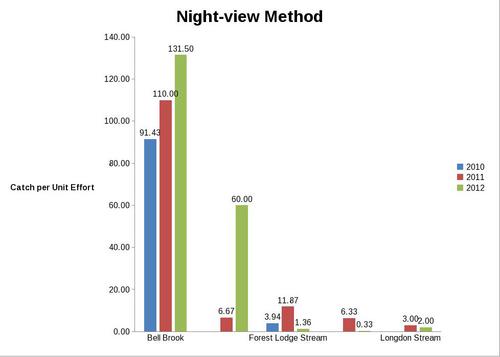

Relative abundance of crayfish was calculated as the number of crayfish per ten refuges searched (Catch per Unit Effort, CPUE) or fifteen-minutes timed night-view, Fig. 07 and 08. The CPUE in Bell Brook increased and the population remained in the very high category. Forest Lodge Stream increased in CPUE using the standard method but decreased using the fifteen-minutes timed night-view method: overall the Forest Lodge crayfish population remained in the low to moderate population abundance category. Kingswood Stream had a decrease in CPUE but remained in the moderate population abundance category. Longdon Stream had a decrease in CPUE and had a negative change in population abundance category from low abundance to none or an undetected population.

Crayfish Population Dynamics

Juvenile white-clawed crayfish (<25mm carapace length) were caught and measured in Bell Brook, Forest Lodge Stream and Kingswood Stream, Table 1. No juvenile white-clawed crayfish (or adults) were caught in Longdon Stream. Juveniles were recorded in Bell Brook, Forest Lodge Stream and Longdon Stream using the night-time torching method, Table 2.

Standard manual survey | ||||||||||

Bell Brook | Forest Lodge Stream | Kingswood Stream | Longdon Stream | |||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2011 | 2012 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Adult | 3 | 14 | 28 | 1 | 25 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Juvenile | 5 | 13 | 19 | 0 | 21 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

Table 1. . Comparison of adult and juvenile white-clawed crayfish caught and measured in four watercourses of the Wyre Forest during three years.

Night viewing survey | ||||||||||

Bell Brook | Forest Lodge Stream | Kingswood Stream | Longdon Stream | |||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2011 | 2012 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Adult | 187 | 305 | 351 | 21 | 66 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| Juvenile | 179 | 291 | 288 | 16 | 20 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

Table 2.. Comparison of adult and juvenile records recorded in four watercourses of the Wyre Forest during three years using night-view survey method.

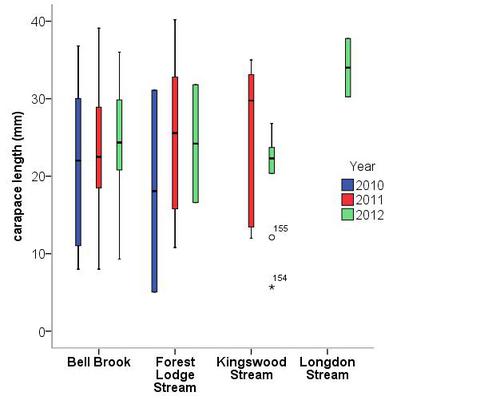

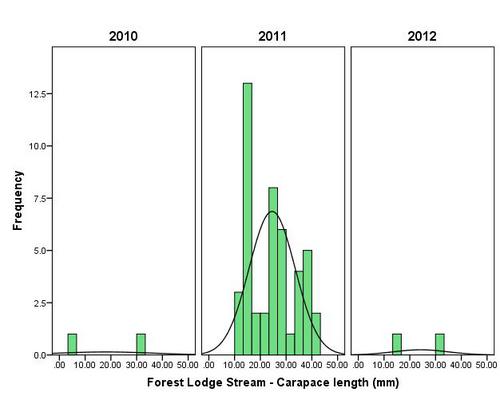

There was no significant difference between the white-clawed crayfish carapace length of individuals caught and measured over the three years in Bell Brook, Forest Lodge Stream and Kingswood Stream (Bell Brook: Kruskal-Wallis test, sig. = 0.592, p = n.s., n = 2; Forest Lodge Stream: Kruskal-Wallis test, sig. = 0.793, p = n.s., n = 2; Kingswood Stream: Kruskal-Wallis test, sig. = 0.178, p = n.s., n = 1), Fig. 09. Neither was there any significant difference between year (2010, 2011 and 2012), watercourse (Bell Brook, Forest Lodge Stream, Kingswood Stream and Longdon Stream) and white-clawed crayfish carapace length (Two-way Anova (with replication) year P-value = .337; watercourse P-value = .278; year*watercourse P-value = .420).

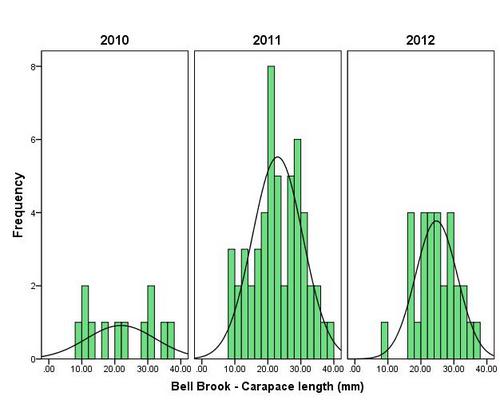

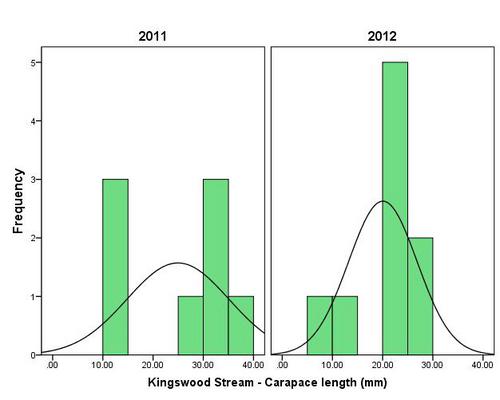

Following two relatively stable years the crayfish population in Bell Brook showed an increase in average carapace size, indicating the possibility of an older population (skewness -0.161), Fig. 10. Fewer individuals were caught and measured in Kingswood Stream but those measured exhibited the same increase in average carapace length suggesting that Kingswood Stream may also have an ageing population (skewness -1.451), Fig. 11 There were too few observations to comment on population status in Forest Lodge Steam (Fig. 12) and Longdon Stream.

All crayfish that were caught were sexed, Table 3. Female and male white-clawed crayfish were recorded in Bell Brook and Kingswood Stream in 2012. However, only female white-clawed crayfish were recorded in Forest Lodge Stream and Longdon Stream.

Bell Brook | Forest Lodge Stream | Kingswood Stream | Longdon Stream | |||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2011 | 2012 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Male | 2 | 19 | 18 | 1 | 29 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | |

| Female | 8 | 33 | 12 | 0 | 14 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | |

Table 3. Comparison of male and female records recorded in four watercourses of the Wyre Forest during three years using standard survey method.

Discussion

There was no change in the geographical range of the white-clawed crayfish in Wyre Forest although there was an overall reduction in white-clawed crayfish observations across the Wyre Forest.

Bell Brook continued to support a very high population of white-clawed crayfish and there was a statistically significant increase in standard daytime manual observations in 2012 when compared with the previous two years. There was a mix of adults, both male and female, and juveniles indicating a healthy population structure although it may be slightly ageing. The results were likely due to favourable environmental conditions in the past twelve months and/or underlying natural population cycles (currently unknown).

Forest Lodge Stream has a small catchment that responds quickly to rainfall but with little storage capacity and as a consequence the white-clawed crayfish population is vulnerable to the peculiarities of the weather. The white-clawed crayfish population was recovering from the drought conditions of 2011 and had a low to moderate population abundance. Juveniles made up at least 40% of the white-clawed crayfish population so whilst no male crayfish were caught and recorded the varied size range indicated that Forest Lodge Stream continued to have a healthy but small population of white-clawed crayfish.

There was no significant change in the white-clawed crayfish population in Kingswood Stream and the presence of juveniles and a varied size range of adults (both male and female) was indicative of a breeding population. Catch per Unit Effort decreased although Kingswood Stream continued to have a moderate population abundance category for white-clawed crayfish. The in-stream duck pond has been removed during the past twelve months. Kingswood Stream had the highest recording of dissolved solids in the water of all four watercourses and levels had increased on 2011 measurements. Water quality remained an issue for the survival of the Kingswood Stream white-clawed crayfish population.

There was negative change in the population condition of white-clawed crayfish in Longdon Stream. No white-clawed crayfish were detected during the standard daytime survey and only six crayfish were recorded at night-time (eight were recorded in 2011). The two crayfish that were caught and measured were both female. No juveniles were recorded. The overall conclusion is that the breeding success and population structure is poor and that there is a problem with recruitment. Water clarity was poor with the second highest recording of dissolved solids in water of all four watercourses. Water quality is likely to be the critical issue for the survival of this population of white-clawed crayfish.

In conclusion, after three years of study there is still only limited information about the way the white-clawed crayfish of the Wyre Forest vary in abundance and spatially over time. The trends will need to be compared over many years and information on long-term variation will only gradually be obtained from continuing the monitoring of crayfish populations in Wyre Forest.

References

Hill, A., 2010. Atlantic Stream Crayfish in Wyre. In: Winnall, R. (Ed.) Wyre Forest Study Group Review 2010.

Hill, A., 2011. Crayfish of Wyre Forest – an update. In: Winnall, R. (Ed.) Wyre Forest Study Group Review 2011.

Peay, S., 2002. A Standardised Survey and Monitoring Protocol for the White-clawed Crayfish in the UK. Life in UK Rivers LIF 02-11-37. EC LIFE Programme, DG Env.D.1., Brussels, Belgium.

Peay, S., 2003. Monitoring the White-clawed Crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes. Conserving Natura 2000 Rivers Monitoring Series No. 1, English Nature, Peterborough.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Wyre Forest Study Group and Forestry Commission who provided local knowledge and access details, Natural England and private landowners for access permissions and the volunteers, especially Mike Averill, Jane Scott and Rosemary Winnall, who assisted with the survey work.

Images

Fig. 011. The location of the crayfish monitoring site in the Wyre Forest showing the four sample watercourses.

Fig. 02. Observations of white-clawed crayfish within four watercourses in the Wyre Forest, Worcestershire between 2010 and 2012.

Fig. 03. Observations of white-clawed crayfish within Bell Brook, Wyre Forest between 2010 and 2012.

Fig. 04. Observations of white-clawed crayfish within Forest Lodge Stream, Wyre Forest between 2010 and 2012

Fig. 02. Observations of white-clawed crayfish within Kingswood Stream, Wyre Forest between 2010 and 2012

Fig. 06. Observations of white-clawed crayfish within Longdon Stream, Wyre Forest between 2010 and 2012.

Fig. 07-1. Comparison of relative abundance of white-clawed crayfish recorded per unit effort searched (ten refugia) between 2010, 2011 and 2012 in four streams within the Wyre Forest.

Fig. 07-2. Comparison of relative abundance of white-clawed crayfish recorded per unit effort searched (ten refugia) between 2010, 2011 and 2012 in four streams within the Wyre Forest.

Fig. 08. Comparison of relative abundance of white-clawed crayfish recorded per unit effort searched (fifteen-minute timed search) between 2010, 2011 and 2012 in four watercourses within the Wyre Forest.

Fig.09: Comparison of white-clawed crayfish carapace length of individuals caught and measured over the three years (2010, 2011 and 2012) in Bell Brook, Forest Lodge Stream, Kingswood Stream and Longdon Stream, Wyre Forest.

Fig. 10: Histogram showing size distribution (carapace length mm) of white-clawed crayfish population in Bell Brook, Wyre Forest in three survey years

Fig. 11: Histogram showing size distribution (carapace length mm) of white-clawed crayfish population in Kingswood Stream, Wyre Forest in three survey years

Fig.12. Histogram showing size distribution (carapace length mm) of white-clawed crayfish population in Forest Lodge Stream, Wyre Forest in two survey years