An account of one Swift nest in Kidderminster

Mike Averill

This is not an in-depth study, but observations of a Swift nest assisted by the installation of a camera. In 2010 a box designed for Swift use (see Swift Conservation web site for information) was finally occupied after being in situ for about seven years. It was fitted on a building in an area where Swifts are present each year and there are usually two other nests within 100 metres of the house. The box is on the east side of the house with the access hole facing down the road to the south. The box is under the eaves and so is not in direct sunshine. The construction is as per normal recommendations but the entrance was fitted at the end purely because it meant that it would be visible to Swifts flying up the road. In the seven years the box had been up there were only a few occasions when it was inspected by Swifts but no Swifts were seen to enter until 2010. Occupation was first noticed in mid July 2010 and at least one chick was seen to fledge that year with a further egg being found later un-hatched. Swifts are hard to observe at nest sites because the adults do not go in and out very often during the day and so a camera is a must. In 2010 a camera was fitted outside the box trained on the nest entrance and this helped to some extent but it was still impossible to tell what was going on inside. With that in mind, in readiness for the 2011 season an infrared camera was fitted inside the box: the sort commonly used in tit nestboxes. Unfortunately the Swifts did not return to the box in 2011.

Interestingly in 2010 the Swifts actually evicted nesting House Sparrows to use the box and in 2012 Sparrows were once again trying to use the box and so in late April the entrance slot was reduced in size to prevent this. To further encourage the use of the box in 2012, a Swift call recording obtained from Swift Conservation was played during early May. This call consists of the screams of Swifts which already have a nest site and is supposed to stimulate other prospective Swifts to investigate. Whether this worked or not it was with great relief that two Swifts were seen to enter the box on 22nd May 2012 and stay in there all morning. Pairing appeared to take place during that time. Prior to that Swifts had been seen in the area from 31st April 2012.

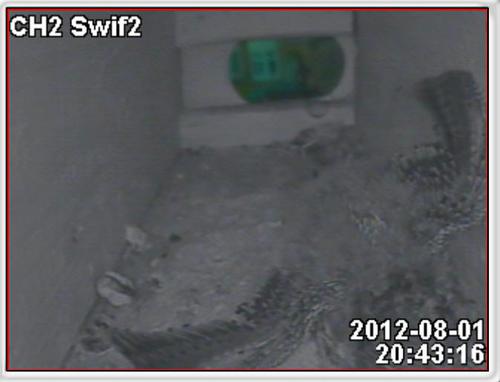

Table 1 shows the observations during the nesting period which produced one fledged nestling. It was a very prolonged period and something may have happened to interrupt the process as there were signs of some disturbance on the 11th June when nesting material was heaved up, and no birds stayed that night which wass the first time that two Swifts had not roosted in the box since the 22nd May. Unfortunately the box wasn’t observed again until the 20th June but the Swifts had returned and they were occupying the box at night. It was a strange year of course weather wise with prolonged cool wet periods and it is easy to speculate that poor conditions had stalled the nesting process. Whatever went on, the routine overnight occupation of the box by two Swifts was observed uninterrupted from the 20th June to the 28th August. It was difficult to see exactly when the egg was laid as the camera angle was not perfect so it was not until the 1st August that the first glimpse of a chick was made. The following 23 days were spent selfishly by the single chick eagerly greeting the adults who returned with foodballs of flies, making a fuss rather like young mammals do on the return of adults with food. Internal cleanliness was good with the adults taking droppings away and the chick reversing kingfisher style to eject faecal material out of the box hole: another confirmation that the end access hole seems to work well. One interesting fact revealed by the camera was that two Swifts used the box each night. Very often it is assumed that the males do not have much contact with the nest site other than bringing food. Assuming that the two in the box were a pair, both male and female had spells brooding the egg. Pair bonding was reinforced by the one sitting on the nest calling loudly if the other one was out collecting food. As soon as the chick had hatched both adults would go out feeding during the day.

| 22/5/2012 | First attempt to enter nest box today. Many entries and two birds were in the box at dusk. Mating appeared to take place. |

| 23/5/2012 | Both birds out all day returning at 21.08 to stay all night |

| 24/5/2012 | Screaming from box at 10:34. Both Swifts in at 21.09 |

| 25/5/2012 | Two birds in nest box at night |

| 26/5/2012 | Two birds in nest box at night |

| 27/5/2012 | Two birds in nest box at 21:00 |

| 28/5/2012 | Two birds in nest box at 08:30 and 22:00 |

| 29/5/2012 | Both birds in and out several times finally entering at 21:15 |

| 30/5/2012 | Two birds in nest box at 21:15 |

| 31/5/2012- 10/6/2012 | Two birds in nest box at night |

| 11/6/2012 | No birds in box overnight |

| 12/6-20/6 | Some sort of disturbance in the box with nesting material being heaved up. Nest was not observed again until 20/6 |

| 20/6/2012 | Two birds screaming from box |

| 21/6/2012 | Two birds in box for night at 18:11 |

| 22/6/2012 | Two birds in box for night at 21:25 |

| 23/6/2012 | Two birds in box for night at 21:30 |

| 24/6/2012 -27/6/2012 | Two birds in box for night |

| 5/7/2012 | Two birds in box for night, one stayed all day |

| 14/7/2012-1/8/2012 | At least one bird sitting all day. Couldn’t see it but an egg had been laid |

| 1/8/2012 | First glimpse of one chick |

| 6/8/2012-20/8/2012 | Chick becoming more feathered, food balls being brought and adults avidly greeted by chick. Wing stretching and press ups by the chick. |

| 20/8/2012 | Chick fully feathered, adults didn’t come back to box at night. Nestling doing press up exercises regularly. |

| 23/8/2012 | No adults returned since 20/8/2012, juvenile climbed out of the box at 18:15, then climbed back in. Finally bailed out at 21:12 and the louse fly jumped off the chick to stay in the box. |

Table. 1. Record of events in the Swift nestbox in 2012.

The Swift Louse Fly Crataerina pallida was observed during the time that Swifts used the box and seemed to show up quite well when the infrared camera was on. When the adult Swifts were in the box for the night the louse flies were quite active during preening. There appeared to be a definite attempt by the louse fly to sit behind the birds head whilst it dealt with its feathers and would dodge from one side to another of the neck as the bird’s head reached around. What was puzzling was why one bird could not deal with the louse fly on its mate as that appeared to be possible as they sat side by side. It is interesting to speculate that perhaps the Swift does not make too much attempt to remove the fly and research has in fact not as yet found any detrimental effect from having the parasites on them.

Recent studies by Walker & Rotherham (2010) on a complex of Swift roosts in a German bridge have found that the mean parasitic load was between one and seven per nest and that louse fly numbers declined throughout the Swift breeding season. Parasite populations were heavily female biased, except for at the initial and final stages of the nestling period. It is in the interests of the fly not to overburden the Swift but they feed every five days with males taking on average 23 mg and females 38 mg of blood on each occasion (Kemper, 1951); this has been calculated as being the equivalent to 5% of an adult Swifts total blood volume.

An interesting feature of this insect is that it does not lay an egg but broods internally before laying a fully formed larva that immediately starts to pupate. When the pupa hatches into an adult it seeks to associate itself with a bird or seeks a nest of young Swifts. Louse flies are of course vertically transmitted ectoparasites only passing on their young to the same family of Swifts and so the relationship is very close. Observing the Swifts in the nest box it was clear that the louse flies stayed on the adult Swifts as they came and went and there didn’t appear to be more than one per adult. It was difficult to be sure of that though as they completely disappeared under feathers but what can be said is that no more than one was ever visible on the adults at any one time.

The literature implies that the pupated louse flies associate themselves with the young chicks as soon as they hatch but some must take up residence on the adults. Doing this they will spend many hours hurtling at up to 70 m.p.h. as the adults search for food and their flat bodies seem well adapted for this. What was most interesting was that the final minutes before the juvenile Swift left the box were observed and when the Swift bailed out for its maiden flight the louse fly was seen to jump off. How that louse fly knew it was time to do that is amazing. After the fledgling had left, the louse fly was clearly visible on the inside wall of the box. The flies would of course not want to go anywhere but would need to deposit the larva to pupate and wait until the following spring when the Swifts return. The other interesting question is how the louse flies that are on the adults know when those adults are not going to return to the box because it is a fact that the adults do desert the young who have to make the long trip to Africa on their own. In my box the juvenile Swift was left for four days on its own before it decided it was time to go.

Swifts now rely heavily on buildings for nest sites in the UK and they are under pressure from home owners as repairs are made to house roofs. Ideally Swifts should be given the same sort of protection that is afforded to bat roosts but it is encouraging that they will use artificial boxes and the hope is that more will be installed by householders in the future. Who would want a world without the scream of Swifts in the summer!

References

Walker, M.D. & Rotherham, I.D. 2010. Characteristics of Crataerina pallida (Diptera: Hippoboscidae) populations; a nest ectoparasite of the common Swift, Apus apus (Aves: Apodidae). Experimental Parasitology,126(4): 451-455.

Kemper, H., 1951. Beobachtungen an Crataerina pallida Latr Und Melophagus ovinus L. (Diptera, Pupipara). Zeitschrift fiir Hygiene (Zoologie) 39:225–259.

Swift Conservation web site www.swift-conservation .org

Images

1 -Two Swifts in the box on the first day

2 - The Louse Fly on an adult

3 - First Sighting of the Chick

4 - The chick reversing up to the entrance to defecate

5 - A Louse Fly on the chick

6 - The young chick probably three weeks old

7 - The first attempt to leave the box failed

8 - Crataerina pallida from wikipedia