Worcestershire Record No. 23 November 2007 pp. 28-30

Steve Davies

Introduction

On the 9th June 2007 I attended a field meeting of the Worcestershire Recorders at Wick Grange Farm near Pershore. As many readers will know Tom Meikle runs this intensive farm and takes a keen interest in the wildlife which occurs there.

The main crops present were runner beans and cereal with smaller fields being given to spring onions. Grants from the Countryside Stewardship Scheme have been used to replant and restore hedgerows, and to plant field margins to reintroduce wildflower meadow habitats and rough grassland, hoping this would be conducive to supporting bird species that rely on the invertebrates and seeds found in the crop and field margins to feed their offspring (O’Connor & Shrubb1986). Weed seeds are also a vital winter food for farmland birds, while the bases of the hedgerows and crops provide nest sites for birds such as Corn Buntings (British Agrochemicals Association 1997).

The farm has in previous years been said to have held good numbers of Corn Buntings. However, it should be noted that there have been no prior surveys undertaken to ascertain exact numbers against which to identify population trends. Since the cessation of sugar beet as a crop Tom was concerned about the effect this might have had on the breeding population of Corn Bunting at Wick Grange Farm.

An appropriate survey methodology was required to identify the number of male Corn Buntings holding territory this year. Owing to polygyny in this species with males being known to have harems of up to 10 females (Donald 1997) it would be difficult to estimate the numbers of females present without more intensive study involving time consuming and disruptive nest finding.

Method

Following discussion with Harry Green it was decided that territory mapping using song registrations of male Corn Buntings was the methodology to be used to identify individual territories, with simultaneous registrations the key to separating each male territory.

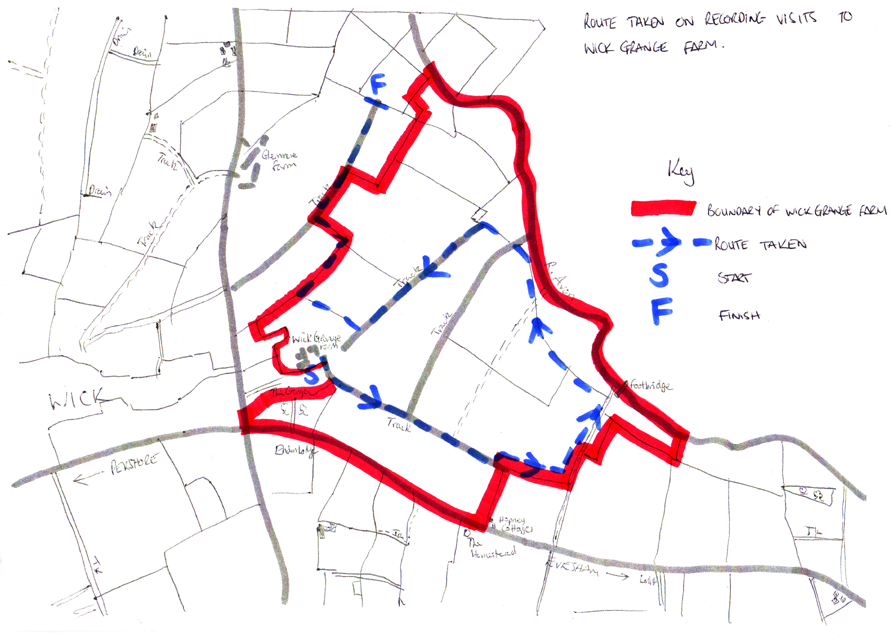

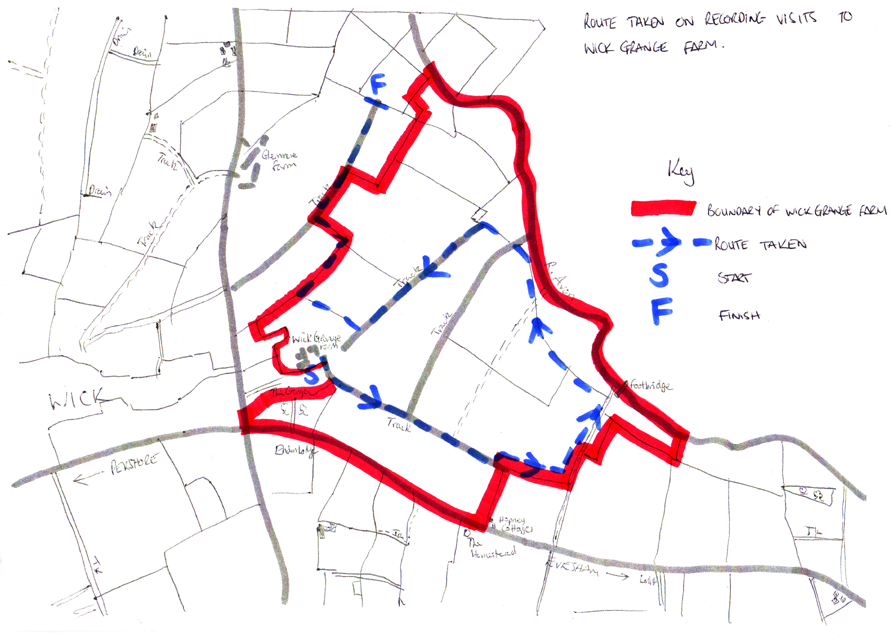

All other Corn Bunting activity was also to be recorded on a simple map of the farm according to Common Birds Census (CBC) methodology which requires five visits (five for a single target species, 7-9 visits for multiple target species) made during the breeding season (Bibby et.al 2000). The route followed is shown on Figure 1 (at the end of this web page).

Recording visits were made between 7am and 11am in the morning during the peak period of bird activity. One evening visit is allowed in this methodology. Each visit consisted of a walk around the farm following the same route which gave good audio and visual acuity and also ensured that all areas of the farm were covered. Consistency is the key to recording good quality data. Each visit was of around two and a half hours duration. Windy, wet weather was avoided, as this reduces bird activity.

The pilot survey visit was made on 9th June and the five survey visits were to continue, if necessary, until the middle of August. CBC fieldwork methodology recommends visits to be no later than the end of July, but due to the late breeding of our target species the survey model was adjusted to take account of this aspect of their breeding biology.

Additionally, the type of song-post from which the song was delivered was also recorded eg-telegraph wire, hedgerow etc., this would prove to be useful in defining territory.

|

Visit |

Date |

Time (hrs BST) |

|

A |

9th June 2007. |

11.00 to 13.00 |

|

B |

24th June 2007. |

07.40 to10.10 |

|

C |

3rd July 2007 |

09.50 to 11.10 |

|

D |

12th July 2007. |

18.30 to 20.30 |

|

E |

25th July 2007. |

08.00 to 10.10 |

Table 1. The dates and times of the recording visits.

Identification of Corn Buntings

Harry Green (2007) gave a pretty accurate description of a Corn Bunting:

Its song is like a short, rapid jangling of a bunch of rusty keys,All I would add to this would be the lack of white in the tail feathers to avoid confusion with Skylark Alauda arvensis (Mullarney et.al 1999). Mullarney et.al (1999) describe the song of male Corn Bunting thus: tuck tuck-zick-zik-zkzkzkrississss. Whichever rendition you prefer, the song is unlikely to be confused with that of any other species when heard in the field. It is normally delivered from a prominent song-post making location of the source of the song an easy task.

Results

It was fortunate that all five visits were undertaken before the end of July due to the heavy rainfall which occurred in the latter part of the breeding season. Indeed, visit E found many parts of the farm waterlogged. I was unable to make the fifth survey visit due to heavy precipitation in the latter part of the breeding season. Therefore I have used the data collected on the pilot survey to give me the five visits required.

The majority of song registrations were recorded in close proximity to areas where the principal components were cereal crop, hedgerows, and field margins. The only song registrations recorded from areas planted with runner beans at any stage of growth were observed from birds perched on overhead telegraph wires.

A variety of song posts were recognised: telegraph wires, isolated trees ,hedgerows, hedgerow trees, cereal crops and weed seed heads that were taller than the surrounding cereal crop.

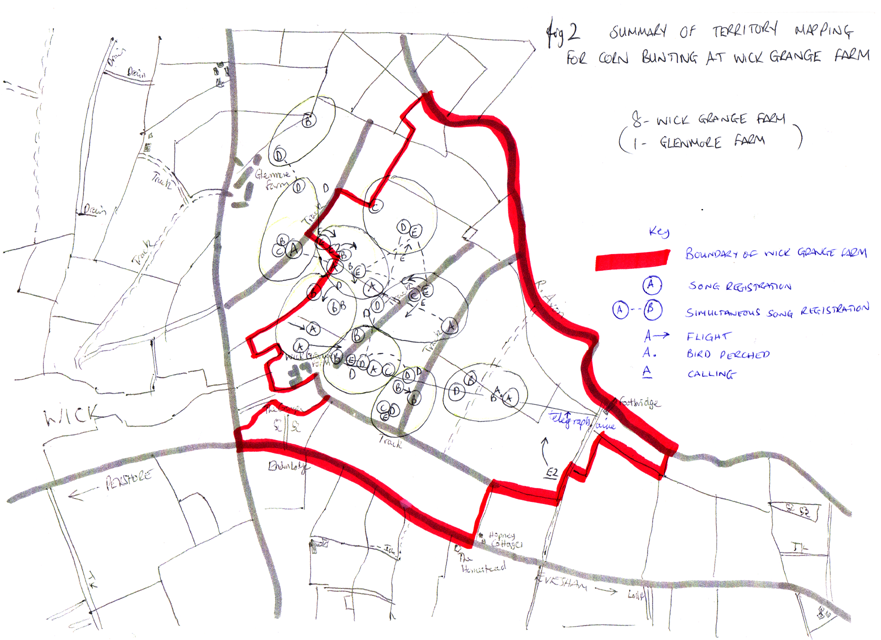

The data from all five mapped visits were transferred onto a master copy for analysis. Each Corn Bunting song/activity was designated a visit letter A,B,C,D or E. Once transfer was completed clusters of registrations were used to define territories (see Figure 2 at the end of this web page).

Based on these clusters of registrations I suggest there were eight male Corn Buntings holding territory on Wick Grange Farm, including one male that favoured an isolated tree as a song-post and whose territory may have been on the periphery of the study area. Interestingly, a male territory was identified on neighbouring Glenmore Farm in a cereal field bisected by a weedy strip.

Discussion

The key factor to consider when determining territoriality in this study was the incidence of simultaneous registrations. The maximum number of males recorded singing simultaneously was four. The other four territories were designated by the following criteria:

a. those birds that were of sufficient distance from other singing males as to be considered holding separate territory.Lilleor (2007) stated that in a study on a farmland area in Denmark he found a mean territory density of between 8.8 and 23.9 per km² in suitable habitat

A future study may benefit from a program of capture of Corn Buntings and the fitting of individual colour ring combinations that could be identified in the field. The value of the data this could yield cannot be overestimated as individual males could be identified with a high degree of confidence and territory density could be more accurately measured.

Conclusions

The managed habitat at Wick Grange Farm appears to be good for Corn Buntings, a species with a patchy distribution (Shrubb 1997) and generally in decline perhaps due to changes in modern agricultural practices (Shrubb 2003).

With this study we have a datum point by which to measure Corn Bunting territory density at Wick Grange Farm in future breeding seasons and will be able to monitor any changes that occur.

However, counting the birds is the easy bit!

To identify the mechanisms that allow Corn Buntings to thrive at this site we must make further study using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and linear multiple regression as used in the Danish farmland study by Lilleor (2007).

I look forward to recording Corn Buntings in 2008.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Tom Meikle for allowing me to carry out this study on his farm and Harry Green for his advice on analysing song registration data.

Figure 1. Route followed at Wick Grange Farm while surveying Corn Bunting Territories

Figure 2. Map of registrations of singing male corn buntings assigned to probable territories

References:

| BIBBY, C.J et.al (2000)Bird Census Techniques. Academic Press. London | |

| BRITISH AGROCHEMICALS ASSOCIATION (1997) Arable Wildlife: Protecting Non-target Species. The British Agrochemicals Association. | |

| DONALD,P.F (1997) The Corn Bunting Millaria calandra in Britain: a review of current status patterns of decline and possible causes. In The ecology and conservation of Corn Buntings Millaria calandra. JNCC | |

| GREEN,G.H (2007) The Corn Bunting. Worcestershire Wildlife News, No. 108. April 2007. Worcestershire Wildlife Trust | |

| LILLEOR,O 2007 Habitat selection by territorial male Corn Buntings Emberiza calandra in a Danish farmland area. Dansk Ornitologisk Forenings Tidsskrift. 101, 79-93. | |

| MULLARNEY K, SVENSSON L, ZETTERSTRÖM D & GRANT P. (1999 ) CollinsBird Guide. HarperCollins. | |

| O’CONNOR,R.J & SHRUBB, M (1986) Farming and Birds. Cambridge University Press. | |

| SHRUBB, M (1997) Historical trends in British and Irish Corn Bunting Millaria calandra populations - evidence for the effects of agricultural change. in The ecology and conservation of Corn Buntings Millaria calandra. JNCC. | |

| SHRUBB,M (2003) Birds, Scythes and Combines: A History of Birds and

Agricultural change. Cambridge University Press. |

| WBRC Home | Worcs Record Listing by Issue | Worcs Record Listing by Subject |